Apontamentos sobre utopia |

|

| Século

XVI Cidade Ideal e Mundo Novo |

Século

XVII Viagem imaginária e utopia científica |

Século XVIII | Século

XIX A Esperança da Cidade Futura |

Século XX |

|

|

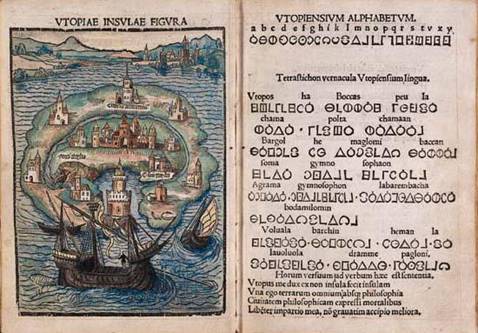

Dando corpo à esperança milenarista, a Utopia do século XVI desenha a cidade ideal a partir da experiência do Novo Mundo. Ela empreende a viagem imaginária tomando como inspiração a viagem de descoberta. Digamos que a o Novo Mundo vem oferecer ao pensamento utópico a longínqua realidade de um tempo e de um espaço afinal tangíveis. Afinal, a idade do ouro existe do outro lado do Atlântico, numa ilha separada do mundo e cujos contornos circunscrevem outras formas de vida.

|

Lá habitam homens que respiram o ar puro e livre das florestas, homens cujos corações acompanham o ritmo do balouçar das árvores, cujos olhos se abrem sempre, cada manhã, em plena inocência.

A beleza física e a pureza moral desses Índios são expressão da sua natureza de seres intocados pelo pecado original. Homens naturais, alegres e amáveis, que habitam mundos harmoniosos que se julgavam perdidos, sem leis, sem regras, sem contrariedades. Crianças crescidas que desprezam o ouro e que por isso o dão com simplicidade aos marinheiros que chegam às suas praias.

Essas figuras arquetípicas aí ficam para sempre a apontar o caminho da da cidade perfeita, da lua, do sol, da cidade futura.

|

|

|

Thomas More o primeiro. É ele quem propõe a palavra Utopia

|

Thomas More

|

|

E a palavra designa, daí em diante, em primeiro lugar uma ilha. Ilha sem parte alguma – Nusquama – ou melhor, em parte incerta. Ilha na qual corre o rio Anhydris (sem água). Que é governada por Ademus (princepe sem povo), habitada pelos Aleopolis (cidadãos sem cidade). Ilha cujo nome – Utopia - remete para uma geografia do impossível, ou melhor, do quase-impossível, nos confins do Mundo Novo, nos alvores da aventura marítima do Ocidente. Por isso o narrador é português de nascimento, um dos 24 marinheiros que Americo Vespúcio terá deixado nas Américas. Por isso esta Utopia, como todas as outras, oscila entre a viagem imaginária e a viagem de descoberta.

|

• Novo género literário ? Simultaneamente, projecção imaginária e ficção realista, análise crítica e texto normativo.

• Versão cristã da República de Platão? Não já contemplativa mas activa.

• Aproximação tímida à abolição da propriedade privada, condenação idealista da moeda, elogio da agricultura, do trabalho igualitário, da paz.

• Formidável declaração do princípio da tolerância religiosa – nenhum homem poderá ser condenado pela defesa da sua religião.

• Mundo ideal e simultaneamente invertido. Perfeito para fazer compreender a imperfeição do mundo real.

Cada época regressará à Utopia de Thomas More para aí encontrar o seu próprio projecto. A Utopia de More é por isso a matriz de todas as utopias. Passadas e futuras.

|

“The island of Utopia is in the middle 200 miles broad, and holds almost at the same breadth over a great part of it; but it grows narrower toward both ends. Its figure is not unlike a crescent: between its horns, the sea comes in eleven miles broad, and |

A voz de Rabelais é a do educador. Simultaneamente mais elaborada, mais risonha e mais radical. Irreverente e livre. Ou livre porque irreverente.

|

Rabelais |

|

|

~ |

« Toute leur vie estoit employée non par loix, statuz ou reigles: mais selon leur vouloir, et franc arbitre. Se levoient du lict, quand bon leur sembloit: beuvoient, mangeoient, travailloient, dormoient, quand le desir leur venoit. Nul ne les esveilloit, nul ne les parforçoit ny à boyre, ny à manger, ny à faire chose aultre quelconques. Ainsi l’avoit estably Gargantua. En

leur reigle n’estoit que ceste clause: |

|

|

« Tant noblement estoient aprins, qu’il n’estoit entre eulx celluy, ne celle, qui ne sceust lire, escripre, chanter, jouer d’instrumens harmonieux, parler de cinq, et six langaiges, et en icelles composer tant en carme, qu'en oraison solue. Jamais ne furent veuz chevaliers tant preux, tant galants, tant dextres à pied, et à cheval, plus verts, mieulx remuants, mieulx maniants touts bastons, que là estoient. Jamais ne furent veues dames tant propres, tant mignonnes, moins fascheuses, plus doctes à la main, à l’agueille, à tout acte muliebre honneste, et libere, que là estoient. Par ceste raison, quand le temps venu estoit, qu'aulcun d’icelle abbaye, ou à la requeste de ses parents, ou pour aultres causes voulust yssir hors, avecq' soy il emmenoit une des dames, celle laquelle l’auroit prins pour son devot, et estoient ensemble mariés. Et si bien avoient vescu à Theleme en devotion, et amytié: encores mieulx la continuoient ilz en mariage: et aultant s'entreaymoient ilz à la fin de leurs jours, comme le premier de leurs nopces » |

Outros descrevem viagens improváveis, desenham ilhas de amores, deixam-se maravilhar pelos relatos de viagens desconhecidas e sobre eles recortam perfis de mundos ideais, de cidades felizes, de repúblicas celestes.

|

Camões Os Lusíadas (1571) |

|

|

Francesco Patrizi La Citta Felice (1553) |

|

Antonio Francesco

Doni Les Mondes Célestes, Terrestres et Infernaux (1558) |

|

|

Lodovico Agostini La Repubblica Immaginaria (1580) |

P. Giovanni Pietro Maffei L'Histoire des Indes Orientales et Occidentales (1589) |

|

|

|

"Quien holgare de entender verdaderos hechos de esta naturaleza, que tan varia y abundante es, tendrá el gusto que da la historia, y tanto mejor historia cuanto los hechos no son por trazas de hombres, sino del Criador: Quien pasare adelante y llegare a entender las causas naturales de los efectos, tendrá el ejercicio de buena filosofía: Quien subiere más en su pensamiento y, mirando al sumo y primer Artífice de todas estas maravillas, gozare de su saber y grandeza, diremos que trata excelente teología. Así que para muchos buenos motivos puede servir la relación de cosas naturales, aunque la bajeza de muchos gustos suele más ordinario parar en lo menos útil, que es un deseo de saber cosas nuevas, que propiamente llamamos curiosidad. |